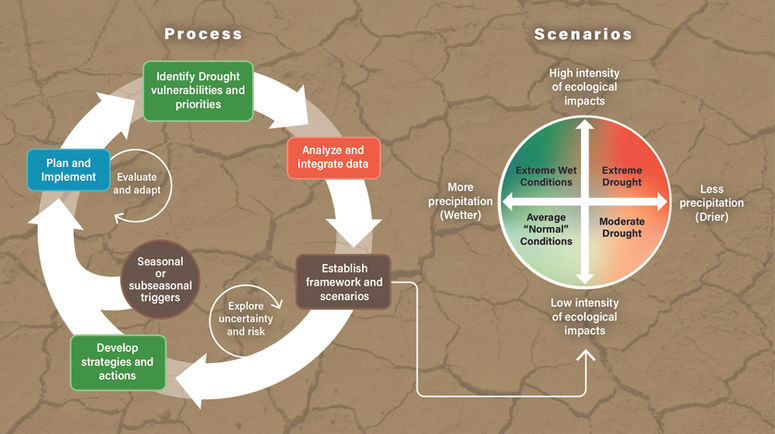

We are seeking a highly qualified and experienced candidate to join our research team and lead research aimed at understanding the dynamic relationships among animal distribution, abundance and landscape structure, composition, configuration and connectivity. Applicants should have strong interest and background in applied ecology, conservation, and spatial analyses. Quantitative proficiency in occupancy, sightability, mark/recapture, connectivity and other relevant quantitative approaches is needed.

Seabird Population Dynamics

Southern California is home to some of the largest breeding colonies of seabirds and coastal/wetland shorebirds. In partnership with CDFW, IEMM provides quantitative expertise to support CDFW’s ongoing efforts to monitor and conserve these populations. Applicants should have strong interest and experience in using long-term seabird datasets, analyzing survey data, population analyses, and quantitative approaches to identify trends and relative impact of biotic and abiotic conditions on population dynamics.

Qualifications

A PhD is required as well as training or experience in ecology, applied conservation science, or related fields. Candidates must demonstrate scholarship, leadership and have at least 5 years of experience conducting ecological research. Experience in interdisciplinary and innovative, integrated research approaches is a plus. Candidates should be able to work both independently and in a collaborative setting with project team members, stakeholders, and partners at a variety of natural resource management organizations, and community organizations. We are excited to welcome candidates with excellent interpersonal skills, strong writing capacity, and a growing publication record. The researchers will be based at SDSU and will work under the direction of Drs. Megan Jennings and Rebecca Lewison. The positions may require travel within California.

Appointment: Appointments will be for two years from start date, contingent upon performance. Starting salary is approximately $66,560 a year plus benefits (DOE). There are no requirements for citizenship.

To apply:

Application review will begin immediately.

- Wildlife Landscape Ecology: Follow this link to apply

- Seabird Population Dynamics: Follow this link to apply

RSS Feed

RSS Feed